The Classical Era in Western Art Music Encompassed the Years Approximately

The Classical menstruation was an era of classical music between roughly 1730 and 1820.[1]

The Classical period falls between the Bizarre and the Romantic periods. Classical music has a lighter, clearer texture than Bizarre music, just a more sophisticated utilize of form. Information technology is mainly homophonic, using a clear melody line over a subordinate chordal accompaniment,[2] only counterpoint was by no means forgotten, peculiarly in liturgical vocal music and, later in the menses, secular instrumental music. It also makes use of fashion galant which emphasized light elegance in place of the Bizarre'southward dignified seriousness and impressive grandeur. Diversity and contrast within a slice became more pronounced than before and the orchestra increased in size, range, and power.

The harpsichord was replaced every bit the main keyboard instrument past the piano (or fortepiano). Different the harpsichord, which plucks strings with quills, pianos strike the strings with leather-covered hammers when the keys are pressed, which enables the performer to play louder or softer (hence the original proper noun "fortepiano," literally "loud soft") and play with more than expression; in contrast, the forcefulness with which a performer plays the harpsichord keys does not change the sound. Instrumental music was considered important by Classical period composers. The principal kinds of instrumental music were the sonata, trio, cord quartet, quintet, symphony (performed by an orchestra) and the solo concerto, which featured a virtuoso solo performer playing a solo piece of work for violin, piano, flute, or another musical instrument, accompanied by an orchestra. Vocal music, such as songs for a vocaliser and piano (notably the work of Schubert), choral works, and opera (a staged dramatic work for singers and orchestra) were also important during this period.

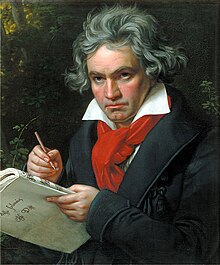

The all-time-known composers from this catamenia are Joseph Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Ludwig van Beethoven, and Franz Schubert; other notable names include Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, Johann Christian Bach, Luigi Boccherini, Domenico Cimarosa, Joseph Martin Kraus, Muzio Clementi, Christoph Willibald Gluck, Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf, André Grétry, Pierre-Alexandre Monsigny, Leopold Mozart, Michael Haydn, Giovanni Paisiello, Johann Baptist Wanhal, François-André Danican Philidor, Niccolò Piccinni, Antonio Salieri, Georg Christoph Wagenseil, Georg Matthias Monn, Johann Gottlieb Graun, Carl Heinrich Graun, Franz Benda, Georg Anton Benda, Johann Georg Albrechtsberger, Mauro Giuliani, Christian Cannabich and the Chevalier de Saint-Georges. Beethoven is regarded either as a Romantic composer or a Classical period composer who was part of the transition to the Romantic era. Schubert is also a transitional figure, equally were Johann Nepomuk Hummel, Luigi Cherubini, Gaspare Spontini, Gioachino Rossini, Carl Maria von Weber, Jan Ladislav Dussek and Niccolò Paganini. The menses is sometimes referred to every bit the era of Viennese Classicism (High german: Wiener Klassik), since Gluck, Haydn, Salieri, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert all worked in Vienna.

Classicism [edit]

In the eye of the 18th century, Europe began to move toward a new style in architecture, literature, and the arts, generally known as Classicism. This style sought to emulate the ideals of Classical antiquity, especially those of Classical Greece.[iii] Classical music used formality and emphasis on order and hierarchy, and a "clearer", "cleaner" mode that used clearer divisions between parts (notably a clear, unmarried melody accompanied by chords), brighter contrasts and "tone colors" (accomplished by the utilize of dynamic changes and modulations to more keys). In contrast with the richly layered music of the Baroque era, Classical music moved towards simplicity rather than complexity. In improver, the typical size of orchestras began to increment,[3] giving orchestras a more than powerful audio.

The remarkable evolution of ideas in "natural philosophy" had already established itself in the public consciousness. In particular, Newton'southward physics was taken as a image: structures should be well-founded in axioms and be both well-articulated and orderly. This taste for structural clarity began to affect music, which moved away from the layered polyphony of the Baroque period toward a style known every bit homophony, in which the tune is played over a subordinate harmony.[3] This move meant that chords became a much more prevalent feature of music, even if they interrupted the melodic smoothness of a unmarried part. Every bit a result, the tonal structure of a piece of music became more audible.

The new style was also encouraged by changes in the economic gild and social structure. Equally the 18th century progressed, the nobility became the master patrons of instrumental music, while public gustation increasingly preferred lighter, funny comic operas. This led to changes in the way music was performed, the nigh crucial of which was the move to standard instrumental groups and the reduction in the importance of the continuo—the rhythmic and harmonic background of a piece of music, typically played by a keyboard (harpsichord or organ) and usually accompanied by a varied group of bass instruments, including cello, double bass, bass viol, and theorbo. I way to trace the pass up of the continuo and its figured chords is to examine the disappearance of the term obbligato, pregnant a mandatory instrumental part in a work of bedchamber music. In Baroque compositions, additional instruments could be added to the continuo group according to the group or leader's preference; in Classical compositions, all parts were specifically noted, though non always notated, so the term "obbligato" became redundant. By 1800, basso continuo was practically extinct, except for the occasional use of a piping organ continuo part in a religious Mass in the early 1800s.

Economic changes also had the effect of altering the balance of availability and quality of musicians. While in the tardily Baroque, a major composer would accept the entire musical resource of a boondocks to draw on, the musical forces bachelor at an aristocratic hunting lodge or small court were smaller and more fixed in their level of ability. This was a spur to having simpler parts for ensemble musicians to play, and in the example of a resident virtuoso group, a spur to writing spectacular, idiomatic parts for sure instruments, as in the case of the Mannheim orchestra, or virtuoso solo parts for particularly skilled violinists or flautists. In addition, the appetite past audiences for a continual supply of new music carried over from the Bizarre. This meant that works had to be performable with, at best, one or ii rehearsals. Even later 1790 Mozart writes most "the rehearsal", with the implication that his concerts would have only one rehearsal.

Since in that location was a greater accent on a single melodic line, there was greater emphasis on notating that line for dynamics and phrasing. This contrasts with the Baroque era, when melodies were typically written with no dynamics, phrasing marks or ornaments, equally it was assumed that the performer would improvise these elements on the spot. In the Classical era, it became more mutual for composers to indicate where they wanted performers to play ornaments such as trills or turns. The simplification of texture made such instrumental item more important, and too made the apply of characteristic rhythms, such as attention-getting opening fanfares, the funeral march rhythm, or the minuet genre, more important in establishing and unifying the tone of a unmarried movement.

The Classical period also saw the gradual development of sonata grade, a set of structural principles for music that reconciled the Classical preference for melodic material with harmonic development, which could be applied beyond musical genres. The sonata itself continued to be the principal form for solo and chamber music, while later in the Classical menses the string quartet became a prominent genre. The symphony course for orchestra was created in this period (this is popularly attributed to Joseph Haydn). The concerto grosso (a concerto for more than one musician), a very pop course in the Baroque era, began to be replaced by the solo concerto, featuring only ane soloist. Composers began to place more importance on the particular soloist's ability to evidence off virtuoso skills, with challenging, fast calibration and arpeggio runs. Nonetheless, some concerti grossi remained, the most famous of which being Mozart'southward Sinfonia Concertante for Violin and Viola in Due east-flat major.

A modern cord quartet. In the 2000s, string quartets from the Classical era are the core of the chamber music literature. From left to right: violin 1, violin 2, cello, viola

Main characteristics [edit]

In the classical period, the theme consists of phrases with contrasting melodic figures and rhythms. These phrases are relatively brief, typically iv bars in length, and tin can occasionally seem thin or terse. The texture is mainly homophonic,[two] with a clear melody above a subordinate chordal accessory, for instance an Alberti bass. This contrasts with the practice in Bizarre music, where a piece or movement would typically have only one musical subject, which would and so be worked out in a number of voices according to the principles of counterpoint, while maintaining a consistent rhythm or metre throughout. Equally a result, Classical music tends to have a lighter, clearer texture than the Baroque. The classical mode draws on the fashion galant, a musical manner which emphasised light elegance in place of the Bizarre'southward dignified seriousness and impressive grandeur.

Structurally, Classical music mostly has a clear musical form, with a well-defined contrast between tonic and dominant, introduced by clear cadences. Dynamics are used to highlight the structural characteristics of the piece. In item, sonata grade and its variants were developed during the early classical period and was frequently used. The Classical approach to structure again contrasts with the Baroque, where a composition would normally move betwixt tonic and dominant and back once again, only through a continual progress of chord changes and without a sense of "arrival" at the new fundamental. While counterpoint was less emphasised in the classical period, it was past no means forgotten, especially later on in the period, and composers even so used counterpoint in "serious" works such as symphonies and string quartets, as well as religious pieces, such every bit Masses.

The classical musical manner was supported by technical developments in instruments. The widespread adoption of equal temperament made classical musical structure possible, by ensuring that cadences in all keys sounded similar. The fortepiano and then the pianoforte replaced the harpsichord, enabling more dynamic contrast and more sustained melodies. Over the Classical period, keyboard instruments became richer, more than sonorous and more powerful.

The orchestra increased in size and range, and became more than standardised. The harpsichord or piping organ basso continuo role in orchestra fell out of utilize between 1750 and 1775, leaving the string section woodwinds became a cocky-independent section, consisting of clarinets, oboes, flutes and bassoons.

While vocal music such as comic opera was pop, great importance was given to instrumental music. The principal kinds of instrumental music were the sonata, trio, string quartet, quintet, symphony, concerto (ordinarily for a virtuoso solo instrument accompanied by orchestra), and calorie-free pieces such as serenades and divertimentos. Sonata course adult and became the most important form. It was used to build up the first movement of most large-scale works in symphonies and string quartets. Sonata grade was besides used in other movements and in single, standalone pieces such equally overtures.

History [edit]

Bizarre/Classical transition c. 1730–1760 [edit]

In his book The Classical Style, author and pianist Charles Rosen claims that from 1755 to 1775, composers groped for a new mode that was more effectively dramatic. In the High Bizarre period, dramatic expression was limited to the representation of individual affects (the "doctrine of affections", or what Rosen terms "dramatic sentiment"). For instance, in Handel's oratorio Jephtha, the composer renders four emotions separately, one for each graphic symbol, in the quartet "O, spare your girl". Eventually this delineation of individual emotions came to be seen as simplistic and unrealistic; composers sought to portray multiple emotions, simultaneously or progressively, within a single grapheme or movement ("dramatic action"). Thus in the finale of human activity 2 of Mozart'due south Die Entführung aus dem Serail, the lovers movement "from joy through suspicion and outrage to final reconciliation."[4]

Musically speaking, this "dramatic action" required more musical variety. Whereas Baroque music was characterized past seamless menstruum within individual movements and largely uniform textures, composers after the Loftier Baroque sought to interrupt this flow with sharp changes in texture, dynamic, harmony, or tempo. Amidst the stylistic developments which followed the High Baroque, the most dramatic came to exist called Empfindsamkeit, (roughly "sensitive style"), and its best-known practitioner was Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach. Composers of this way employed the above-discussed interruptions in the about sharp manner, and the music can sound illogical at times. The Italian composer Domenico Scarlatti took these developments further. His more than five hundred single-movement keyboard sonatas also incorporate abrupt changes of texture, only these changes are organized into periods, balanced phrases that became a hallmark of the classical style. However, Scarlatti's changes in texture still audio sudden and unprepared. The outstanding achievement of the great classical composers (Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven) was their ability to make these dramatic surprises sound logically motivated, so that "the expressive and the elegant could join hands."[4]

Between the death of J. South. Bach and the maturity of Haydn and Mozart (roughly 1750–1770), composers experimented with these new ideas, which tin be seen in the music of Bach'southward sons. Johann Christian developed a style which we at present call Roccoco, comprising simpler textures and harmonies, and which was "charming, undramatic, and a little empty." As mentioned previously, Carl Philipp Emmanuel sought to increase drama, and his music was "violent, expressive, brilliant, continuously surprising, and frequently breathless." And finally Wilhelm Friedemann, J.S. Bach's eldest son, extended Baroque traditions in an idiomatic, anarchistic way.[five]

At first the new style took over Baroque forms—the ternary da capo aria, the sinfonia and the concerto—but equanimous with simpler parts, more than notated ornamentation, rather than the improvised ornaments that were common in the Bizarre era, and more emphatic division of pieces into sections. However, over time, the new aesthetic caused radical changes in how pieces were put together, and the basic formal layouts changed. Composers from this period sought dramatic effects, striking melodies, and clearer textures. One of the big textural changes was a shift abroad from the complex, dense polyphonic fashion of the Baroque, in which multiple interweaving melodic lines were played simultaneously, and towards homophony, a lighter texture which uses a clear single melody line accompanied by chords.

Baroque music generally uses many harmonic fantasies and polyphonic sections that focus less on the construction of the musical piece, and there was less accent on clear musical phrases. In the classical catamenia, the harmonies became simpler. However, the structure of the piece, the phrases and small-scale melodic or rhythmic motives, became much more than important than in the Baroque catamenia.

Muzio Clementi'southward Sonata in G minor, No. three, Op. l, "Didone abbandonata", adagio motion

Another important break with the past was the radical overhaul of opera by Christoph Willibald Gluck, who cut away a keen deal of the layering and improvisational ornaments and focused on the points of modulation and transition. By making these moments where the harmony changes more of a focus, he enabled powerful dramatic shifts in the emotional color of the music. To highlight these transitions, he used changes in instrumentation (orchestration), melody, and mode. Among the most successful composers of his time, Gluck spawned many emulators, including Antonio Salieri. Their emphasis on accessibility brought huge successes in opera, and in other vocal music such every bit songs, oratorios, and choruses. These were considered the most of import kinds of music for performance and hence enjoyed greatest public success.

The phase between the Bizarre and the rising of the Classical (around 1730), was abode to various competing musical styles. The diversity of artistic paths are represented in the sons of Johann Sebastian Bach: Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, who continued the Baroque tradition in a personal way; Johann Christian Bach, who simplified textures of the Baroque and most conspicuously influenced Mozart; and Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, who composed passionate and sometimes violently eccentric music of the Empfindsamkeit move. Musical culture was defenseless at a crossroads: the masters of the older mode had the technique, but the public hungered for the new. This is one of the reasons C. P. Due east. Bach was held in such high regard: he understood the older forms quite well and knew how to present them in new garb, with an enhanced variety of form.

1750–1775 [edit]

By the late 1750s there were flourishing centers of the new style in Italian republic, Vienna, Mannheim, and Paris; dozens of symphonies were composed and there were bands of players associated with musical theatres. Opera or other song music accompanied by orchestra was the feature of most musical events, with concertos and symphonies (arising from the overture) serving as instrumental interludes and introductions for operas and church building services. Over the form of the Classical period, symphonies and concertos developed and were presented independently of vocal music.

Mozart wrote a number of divertimentos, light instrumental pieces designed for entertainment. This is the second movement of his Divertimento in E-flat major, 1000. 113.

The "normal" orchestra ensemble—a torso of strings supplemented by winds—and movements of particular rhythmic character were established by the late 1750s in Vienna. However, the length and weight of pieces was withal prepare with some Baroque characteristics: private movements nonetheless focused on one "impact" (musical mood) or had only one sharply contrasting middle section, and their length was not significantly greater than Baroque movements. There was non yet a clearly enunciated theory of how to compose in the new mode. It was a moment ripe for a breakthrough.

The starting time great master of the style was the composer Joseph Haydn. In the late 1750s he began composing symphonies, and past 1761 he had composed a triptych (Morning time, Noon, and Evening) solidly in the contemporary way. As a vice-Kapellmeister and later Kapellmeister, his output expanded: he composed over twoscore symphonies in the 1760s alone. And while his fame grew, as his orchestra was expanded and his compositions were copied and disseminated, his vocalization was merely ane among many.

While some scholars suggest that Haydn was overshadowed by Mozart and Beethoven, information technology would exist difficult to overstate Haydn's axis to the new style, and therefore to the future of Western art music as a whole. At the time, before the pre-eminence of Mozart or Beethoven, and with Johann Sebastian Bach known primarily to connoisseurs of keyboard music, Haydn reached a identify in music that set him to a higher place all other composers except perhaps the Baroque era's George Frideric Handel. Haydn took existing ideas, and radically altered how they functioned—earning him the titles "father of the symphony" and "male parent of the string quartet".

One of the forces that worked as an impetus for his pressing forward was the starting time stirring of what would after be called Romanticism—the Sturm und Drang, or "storm and stress" stage in the arts, a short period where obvious and dramatic emotionalism was a stylistic preference. Haydn accordingly wanted more dramatic dissimilarity and more emotionally highly-seasoned melodies, with sharpened character and individuality in his pieces. This period faded away in music and literature: still, it influenced what came afterwards and would eventually be a component of aesthetic gustatory modality in later on decades.

The Farewell Symphony, No. 45 in F ♯ pocket-sized, exemplifies Haydn's integration of the differing demands of the new fashion, with surprising abrupt turns and a long tiresome adagio to end the work. In 1772, Haydn completed his Opus 20 set of vi cord quartets, in which he deployed the polyphonic techniques he had gathered from the previous Baroque era to provide structural coherence capable of holding together his melodic ideas. For some, this marks the offset of the "mature" Classical style, in which the period of reaction confronting late Bizarre complexity yielded to a period of integration Baroque and Classical elements.

1775–1790 [edit]

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, posthumous painting by Barbara Krafft in 1819

Haydn, having worked for over a decade as the music director for a prince, had far more than resources and scope for composing than most other composers. His position too gave him the ability to shape the forces that would play his music, as he could select skilled musicians. This opportunity was not wasted, equally Haydn, beginning quite early on his career, sought to press forward the technique of building and developing ideas in his music. His adjacent important breakthrough was in the Opus 33 cord quartets (1781), in which the melodic and the harmonic roles segue amidst the instruments: it is often momentarily unclear what is tune and what is harmony. This changes the way the ensemble works its way between dramatic moments of transition and climactic sections: the music flows smoothly and without obvious break. He then took this integrated style and began applying it to orchestral and song music.

Haydn'southward gift to music was a way of composing, a way of structuring works, which was at the aforementioned fourth dimension in accord with the governing artful of the new fashion. However, a younger contemporary, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, brought his genius to Haydn'due south ideas and practical them to two of the major genres of the day: opera, and the virtuoso concerto. Whereas Haydn spent much of his working life equally a court composer, Mozart wanted public success in the concert life of cities, playing for the general public. This meant he needed to write operas and write and perform virtuoso pieces. Haydn was not a virtuoso at the international touring level; nor was he seeking to create operatic works that could play for many nights in front of a large audition. Mozart wanted to achieve both. Moreover, Mozart besides had a taste for more chromatic chords (and greater contrasts in harmonic language generally), a greater beloved for creating a welter of melodies in a unmarried piece of work, and a more Italianate sensibility in music as a whole. He constitute, in Haydn's music and afterwards in his study of the polyphony of J.S. Bach, the means to subject area and enrich his creative gifts.

The Mozart family c. 1780. The portrait on the wall is of Mozart'southward female parent.

Mozart rapidly came to the attention of Haydn, who hailed the new composer, studied his works, and considered the younger man his only truthful peer in music. In Mozart, Haydn found a greater range of instrumentation, dramatic effect and melodic resource. The learning relationship moved in both directions. Mozart also had a slap-up respect for the older, more experienced composer, and sought to acquire from him.

Mozart'southward arrival in Vienna in 1780 brought an acceleration in the development of the Classical manner. There, Mozart captivated the fusion of Italianate brilliance and Germanic cohesiveness that had been brewing for the previous 20 years. His own sense of taste for flashy brilliances, rhythmically circuitous melodies and figures, long cantilena melodies, and virtuoso flourishes was merged with an appreciation for formal coherence and internal connectedness. It is at this point that war and economical inflation halted a trend to larger orchestras and forced the disbanding or reduction of many theater orchestras. This pressed the Classical manner inwards: toward seeking greater ensemble and technical challenges—for example, handful the melody across woodwinds, or using a melody harmonized in thirds. This process placed a premium on small ensemble music, chosen sleeping accommodation music. It also led to a trend for more public performance, giving a further boost to the cord quartet and other small ensemble groupings.

It was during this decade that public taste began, increasingly, to recognize that Haydn and Mozart had reached a high standard of composition. By the time Mozart arrived at historic period 25, in 1781, the ascendant styles of Vienna were recognizably connected to the emergence in the 1750s of the early Classical style. By the end of the 1780s, changes in performance practice, the relative standing of instrumental and vocal music, technical demands on musicians, and stylistic unity had become established in the composers who imitated Mozart and Haydn. During this decade Mozart composed his most famous operas, his half dozen late symphonies that helped to redefine the genre, and a cord of piano concerti that still stand at the pinnacle of these forms.

Ane composer who was influential in spreading the more serious style that Mozart and Haydn had formed is Muzio Clementi, a gifted virtuoso pianist who tied with Mozart in a musical "duel" before the emperor in which they each improvised on the piano and performed their compositions. Clementi's sonatas for the piano circulated widely, and he became the most successful composer in London during the 1780s. Also in London at this fourth dimension was January Ladislav Dussek, who, similar Clementi, encouraged piano makers to extend the range and other features of their instruments, and then fully exploited the newly opened up possibilities. The importance of London in the Classical catamenia is oftentimes overlooked, but it served as the home to the Broadwood'due south factory for piano manufacturing and as the base for composers who, while less notable than the "Vienna School", had a decisive influence on what came later. They were composers of many fine works, notable in their own right. London'south taste for virtuosity may well have encouraged the complex passage work and extended statements on tonic and dominant.

Around 1790–1820 [edit]

When Haydn and Mozart began composing, symphonies were played as single movements—before, betwixt, or as interludes within other works—and many of them lasted merely ten or twelve minutes; instrumental groups had varying standards of playing, and the continuo was a primal role of music-making.

In the intervening years, the social world of music had seen dramatic changes. International publication and touring had grown explosively, and concert societies formed. Notation became more specific, more descriptive—and schematics for works had been simplified (all the same became more varied in their exact working out). In 1790, just before Mozart's death, with his reputation spreading rapidly, Haydn was poised for a series of successes, notably his belatedly oratorios and London symphonies. Composers in Paris, Rome, and all over Frg turned to Haydn and Mozart for their ideas on course.

In the 1790s, a new generation of composers, born around 1770, emerged. While they had grown up with the earlier styles, they heard in the contempo works of Haydn and Mozart a vehicle for greater expression. In 1788 Luigi Cherubini settled in Paris and in 1791 equanimous Lodoiska, an opera that raised him to fame. Its style is conspicuously cogitating of the mature Haydn and Mozart, and its instrumentation gave it a weight that had not nonetheless been felt in the yard opera. His gimmicky Étienne Méhul extended instrumental effects with his 1790 opera Euphrosine et Coradin, from which followed a series of successes. The terminal push towards change came from Gaspare Spontini, who was securely admired by future romantic composers such equally Weber, Berlioz and Wagner. The innovative harmonic linguistic communication of his operas, their refined instrumentation and their "enchained" airtight numbers (a structural pattern which was later adopted by Weber in Euryanthe and from him handed down, through Marschner, to Wagner), formed the ground from which French and German romantic opera had its ancestry.

The most fateful of the new generation was Ludwig van Beethoven, who launched his numbered works in 1794 with a gear up of three piano trios, which remain in the repertoire. Somewhat younger than the others, though as achieved because of his youthful study under Mozart and his native virtuosity, was Johann Nepomuk Hummel. Hummel studied under Haydn every bit well; he was a friend to Beethoven and Franz Schubert. He concentrated more than on the piano than any other instrument, and his time in London in 1791 and 1792 generated the composition and publication in 1793 of three pianoforte sonatas, opus 2, which idiomatically used Mozart's techniques of avoiding the expected cadence, and Clementi's sometimes modally uncertain virtuoso figuration. Taken together, these composers can exist seen as the vanguard of a broad alter in style and the middle of music. They studied one another's works, copied one another's gestures in music, and on occasion behaved similar quarrelsome rivals.

The crucial differences with the previous wave can exist seen in the downward shift in melodies, increasing durations of movements, the acceptance of Mozart and Haydn as paradigmatic, the greater use of keyboard resources, the shift from "song" writing to "pianistic" writing, the growing pull of the minor and of modal ambiguity, and the increasing importance of varying accompanying figures to bring "texture" forward as an element in music. In short, the late Classical was seeking music that was internally more complex. The growth of concert societies and amateur orchestras, marking the importance of music every bit function of middle-form life, contributed to a booming market for pianos, piano music, and virtuosi to serve as exemplars. Hummel, Beethoven, and Clementi were all renowned for their improvising.

The straight influence of the Bizarre continued to fade: the figured bass grew less prominent equally a means of belongings functioning together, the performance practices of the mid-18th century continued to die out. However, at the same time, complete editions of Baroque masters began to become bachelor, and the influence of Baroque style connected to grow, particularly in the ever more expansive utilise of brass. Another feature of the menses is the growing number of performances where the composer was non nowadays. This led to increased particular and specificity in annotation; for example, there were fewer "optional" parts that stood separately from the chief score.

The force of these shifts became apparent with Beethoven'south 3rd Symphony, given the name Eroica, which is Italian for "heroic", past the composer. Every bit with Stravinsky's The Rite of Bound, information technology may not have been the first in all of its innovations, but its aggressive use of every part of the Classical style set it apart from its contemporary works: in length, ambition, and harmonic resources every bit well.

Showtime Viennese School [edit]

The Starting time Viennese School is a name generally used to refer to three composers of the Classical period in late-18th-century Vienna: Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. Franz Schubert is occasionally added to the list.

In German-speaking countries, the term Wiener Klassik (lit. Viennese classical era/art) is used. That term is often more broadly applied to the Classical era in music every bit a whole, equally a ways to distinguish it from other periods that are colloquially referred to equally classical, namely Baroque and Romantic music.

The term "Viennese School" was beginning used by Austrian musicologist Raphael Georg Kiesewetter in 1834, although he just counted Haydn and Mozart as members of the schoolhouse. Other writers followed suit, and eventually Beethoven was added to the listing.[half dozen] The designation "kickoff" is added today to avoid confusion with the 2nd Viennese School.

Whilst, Schubert apart, these composers certainly knew each other (with Haydn and Mozart even existence occasional chamber-music partners), in that location is no sense in which they were engaged in a collaborative attempt in the sense that one would associate with 20th-century schools such every bit the 2d Viennese Schoolhouse, or Les Six. Nor is there whatsoever significant sense in which one composer was "schooled" by another (in the way that Berg and Webern were taught by Schoenberg), though it is true that Beethoven for a time received lessons from Haydn.

Attempts to extend the First Viennese School to include such later figures as Anton Bruckner, Johannes Brahms, and Gustav Mahler are but journalistic, and never encountered in academic musicology.

Classical influence on later composers [edit]

Musical eras and their prevalent styles, forms and instruments seldom disappear at once; instead, features are replaced over fourth dimension, until the old arroyo is just felt as "one-time-fashioned". The Classical manner did not "die" suddenly; rather, it gradually got phased out nether the weight of changes. To requite only 1 case, while information technology is generally stated that the Classical era stopped using the harpsichord in orchestras, this did not happen all suddenly at the commencement of the Classical era in 1750. Rather, orchestras slowly stopped using the harpsichord to play basso continuo until the practice was discontinued past the end of the 1700s.

One crucial alter was the shift towards harmonies centering on "flatward" keys: shifts in the subdominant direction[ clarification needed ]. In the Classical way, major key was far more common than pocket-size, chromaticism being moderated through the use of "sharpward" modulation (e.g., a slice in C major modulating to Chiliad major, D major, or A major, all of which are keys with more sharps). Also, sections in the minor mode were often used for contrast. Outset with Mozart and Clementi, there began a creeping colonization of the subdominant region (the ii or IV chord, which in the key of C major would be the keys of d minor or F major). With Schubert, subdominant modulations flourished after being introduced in contexts in which earlier composers would have confined themselves to dominant shifts (modulations to the dominant chord, e.g., in the central of C major, modulating to G major). This introduced darker colors to music, strengthened the small-scale manner, and made structure harder to maintain. Beethoven contributed to this past his increasing use of the quaternary as a consonance, and modal ambivalence—for instance, the opening of the Symphony No. 9 in D minor.

Ludwig van Beethoven, Franz Schubert, Carl Maria von Weber, and John Field are among the near prominent in this generation of "Proto-Romantics", forth with the young Felix Mendelssohn. Their sense of form was strongly influenced by the Classical way. While they were not yet "learned" composers (imitating rules which were codification by others), they directly responded to works by Haydn, Mozart, Clementi, and others, as they encountered them. The instrumental forces at their disposal in orchestras were also quite "Classical" in number and variety, permitting similarity with Classical works.

Notwithstanding, the forces destined to end the concord of the Classical style gathered forcefulness in the works of many of the above composers, specially Beethoven. The most commonly cited ane is harmonic innovation. Too important is the increasing focus on having a continuous and rhythmically uniform accompanying figuration: Beethoven's Moonlight Sonata was the model for hundreds of later pieces—where the shifting movement of a rhythmic figure provides much of the drama and interest of the work, while a tune drifts above information technology. Greater knowledge of works, greater instrumental expertise, increasing multifariousness of instruments, the growth of concert societies, and the unstoppable domination of the increasingly more powerful pianoforte (which was given a bolder, louder tone by technological developments such as the apply of steel strings, heavy cast-atomic number 26 frames and sympathetically vibrating strings) all created a huge audition for sophisticated music. All of these trends contributed to the shift to the "Romantic" style.

Drawing the line betwixt these ii styles is very hard: some sections of Mozart's afterward works, taken solitary, are indistinguishable in harmony and orchestration from music written lxxx years afterward—and some composers continued to write in normative Classical styles into the early on 20th century. Fifty-fifty earlier Beethoven's death, composers such equally Louis Spohr were self-described Romantics, incorporating, for case, more extravagant chromaticism in their works (eastward.g., using chromatic harmonies in a slice's chord progression). Conversely, works such equally Schubert'southward Symphony No. 5, written during the chronological stop of the Clasaical era and dawn of the Romantic era, exhibit a deliberately anachronistic creative paradigm, harking back to the compositional mode of several decades before.

Nevertheless, Vienna's fall as the most of import musical center for orchestral limerick during the late 1820s, precipitated by the deaths of Beethoven and Schubert, marked the Classical manner'due south concluding eclipse—and the terminate of its continuous organic development of one composer learning in close proximity to others. Franz Liszt and Frédéric Chopin visited Vienna when they were young, only they then moved on to other cities. Composers such as Carl Czerny, while securely influenced by Beethoven, too searched for new ideas and new forms to incorporate the larger earth of musical expression and operation in which they lived.

Renewed interest in the formal remainder and restraint of 18th century classical music led in the early on 20th century to the evolution of so-called Neoclassical fashion, which numbered Stravinsky and Prokofiev amongst its proponents, at to the lowest degree at certain times in their careers.

Classical period instruments [edit]

Fortepiano past Paul McNulty after Walter & Sohn, c. 1805

Guitar [edit]

The Baroque guitar, with four or v sets of double strings or "courses" and elaborately decorated soundhole, was a very different instrument from the early classical guitar which more closely resembles the modern instrument with the standard six strings. Judging past the number of instructional manuals published for the instrument – over three hundred texts were published by over two hundred authors between 1760 and 1860 – the classical catamenia marked a aureate age for guitar.[seven]

Strings [edit]

In the Baroque era, there was more diverseness in the bowed stringed instruments used in ensembles, with instruments such as the viola d'amore and a range of fretted viols being used, ranging from small viols to large bass viols. In the Classical menstruation, the cord section of the orchestra was standardized as only 4 instruments:

- Violin (in orchestras and bedchamber music, typically in that location are first violins and second violins, with the old playing the tune and/or a higher line and the latter playing either a countermelody, a harmony role, a role below the first violin line in pitch, or an accompaniment line)

- Viola (the alto voice of the orchestral string department and cord quartet; it often performs "inner voices", which are accompaniment lines which make full in the harmony of the piece)

- Cello (the cello plays two roles in Classical era music; at times it is used to play the bassline of the piece, typically doubled past the double basses [Note: When cellos and double basses read the same bassline, the basses play an octave beneath the cellos, because the bass is a transposing instrument]; and at other times information technology performs melodies and solos in the lower annals)

- Double bass (the bass typically performs the lowest pitches in the string section in gild to provide the bassline for the slice)

In the Baroque era, the double bass players were not normally given a separate office; instead, they typically played the same basso continuo bassline that the cellos and other low-pitched instruments (e.g., theorbo, serpent wind musical instrument, viols), albeit an octave below the cellos, because the double bass is a transposing musical instrument that sounds one octave lower than it is written. In the Classical era, some composers continued to write only 1 bass office for their symphony, labeled "bassi"; this bass part was played by cellists and double bassists. During the Classical era, some composers began to give the double basses their ain role.

Woodwinds [edit]

- Basset clarinet

- Basset horn

- Clarinette d'amour

- Classical clarinet

- Chalumeau

- Flute

- Oboe

- Bassoon

Percussion [edit]

- Timpani

- "Turkish music":

- Bass drum

- Cymbals

- Triangle

Keyboards [edit]

- Clavichord

- Fortepiano (the forerunner to the modern piano)

- Piano

- Harpsichord, the standard Baroque era basso continuo keyboard instrument, was used until the 1750s, later on which fourth dimension it was gradually phased out, and replaced with the fortepiano then the pianoforte. By the early 1800s, the harpsichord was no longer used.

Brasses [edit]

- Buccin

- Ophicleide – replacement for the "serpent", a bass wind instrument that was the forerunner of the tuba

- French horn

- Trumpet

- Trombone

See too [edit]

- List of Classical-era composers

Notes [edit]

- ^ Burton, Anthony (2002). A Performer's Guide to the Music of the Classical Period. London: Associated Board of the Purple Schools of Music. p. 3. ISBN978-i-86096-1939.

- ^ a b Blume, Friedrich. Classic and Romantic Music: A Comprehensive Survey. New York: W. West. Norton, 1970

- ^ a b c Kamien, Roger. Music: An Appreciation. 6th. New York: McGraw Hill, 2008. Print.

- ^ a b Rosen, Charles. The Classical Style, pp. 43–44. New York: Westward. W. Norton & Company, 1998

- ^ Rosen, Charles. The Classical Style, pp. 44. New York: West. Westward. Norton & Company, 1998

- ^ Heartz, Daniel & Brownish, Bruce Alan (2001). "Classical". In Sadie, Stanley & Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan.

- ^ Stenstadvold, Erik. An Annotated Bibliography of Guitar Methods, 1760–1860 (Hillsdale, New York: Pendragon Printing, 2010), 11.

Further reading [edit]

- Downs, Philip Thousand. (1992). Classical Music: The Era of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, quaternary vol of Norton Introduction to Music History. Westward. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-95191-10 (hardcover).

- Grout, Donald Jay; Palisca, Claude 5. (1996). A History of Western Music, Fifth Edition. Due west. Due west. Norton. ISBN 0-393-96904-5 (hardcover).

- Hanning, Barbara Russano; Grout, Donald Jay (1998 rev. 2006). Concise History of Western Music. Westward. Due west. Norton. ISBN 0-393-92803-9 (hardcover).

- Kennedy, Michael (2006), The Oxford Lexicon of Music, 985 pages, ISBN 0-xix-861459-4

- Lihoreau, Tim; Fry, Stephen (2004). Stephen Fry'south Incomplete and Utter History of Classical Music. Boxtree. ISBN 978-0-7522-2534-0

- Rosen, Charles (1972 expanded 1997). The Classical Style. New York: Due west. Due west. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-04020-iii (expanded edition with CD, 1997)

- Taruskin, Richard (2005, rev. Paperback version 2009). Oxford History of Western Music. Oxford University Press (The states). ISBN 978-0-xix-516979-nine (Hardback), ISBN 978-0-nineteen-538630-1 (Paperback)

External links [edit]

- Classical Internet – Classical music reference site

- Free scores by various classical composers at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Classical_period_(music)

0 Response to "The Classical Era in Western Art Music Encompassed the Years Approximately"

Post a Comment